Access to Books

Posted: April 14th, 2014 | Author: Michael Goldstein | | 3 Comments »

If you give kids access to books they like, along with “connective tissue” (follow-up by staff), can you get them to read more out of school?

If you can increase the amount that kids read out of school, do they do better in school?

In 2013 I ran a small RCT at MATCH, with Ray Schleck, to answer the first question.

Blog 1 is here.

Blog 2 is here.

That high-dosage reading assumption is now baked into Match Next, the blended learning school I designed in 2012. But it will take a long time to see the fruits bear out. Or not. Moreover, since there are other things happening at Match Next, including more in-class reading than in our regular “flagship” Match schools, the pleasure reading effect will be hard to tease out.

So here I’m digging into published research.

Again, can you stimulate kids to read a ton (through a combo of access and teacher/school stuff) out of normal class time; and if the kids do read a ton, will they do better on standardized tests in English, and possibly in other subjects, like social studies, science, or even math (word problems)?

I’ve been looking for such evidence. This blog is my first effort to slog through some of it. I hope to get corrected and then refine my understanding.

Surprisingly, good evidence here seems hard to come by.

There’s lots of data that suggests a connection.

1. In research on the achievement gap, “the number of books in the home” is closely related to literacy levels.

(Here is Roland Fryer’s and Steve Levitt’s paper on that topic. Here is a very interesting mathematical follow-up note from Kevin Lang.)

But of course the books themselves are not causal.

As a thought experiment, what if you simply sent a box of 100 books to a family that had, say, 100 at baseline? Would student achievement change? I don’t think it’d move things much. Though I wonder if this has ever been done.

The “presence of books” seem to be related to “parent effect” in a number of ways, including time spent read to small kids, modeling reading for older kids, and plenty of non-book behaviors like the quality and amount of spoken language at home, trips to the museum, and so forth. In fact, we know that spoken language is a big builder of vocab. And it makes sense that parents who have more books in the house speak in longer, complex sentences to their kids; ask more questions; etc.

2. Scholastic is a large book publishing company. Here is their take on things:

We’ve long known of the life-enhancing effects of reading. But how do we help all students become strong readers? In 1998, leading literacy researcher Jeff McQuillan; issued this remarkable statement: “An analysis of a national data set of nearly 100,000 U.S. school children found that access to printed materials—and not poverty—is the critical variable affecting reading acquisition.”

It’s that simple: When students have access to books they enjoy reading, they read. And when they read, they become more accomplished readers. Since McQuillan’s revelation, data from numerous studies has confirmed the importance of access to books and the engaged reading it enables, particularly for students from economically challenged households:

According to a 2012 paper by Stephen Krashen, Syying Lee, and Jeff McQuillan, “access to books in some cases had a larger impact on reading achievement test scores than poverty . . . This suggests that providing more access to books can mitigate the effect of poverty on reading achievement, a conclusion consistent with other recent results (Achterman 2008; Evans, Kelley, Sikora, and Treiman 2010; Schubert and Becker 2010). This result is of enormous practical importance [as] children of poverty typically have little access to books (Krashen 2004).

A number of studies confirm that when given access to engaging reading material, most children and adolescents take full advantage. More access to books results in more reading; in fact, sometimes a single, brief exposure to good reading material results in a lifelong love affair with books—also known as the “Harry Potter effect” (Cho and Krashen 2002; Krashen 2007).

In 2007 Krashen wrote that “‘reluctant’ readers are often those who have little access to books . . . the most serious problem with current literacy campaigns is that they ignore, and even divert attention from, the real problem: lack of access to books for children of poverty.”

Let me walk this through. I don’t think “it’s that simple.”

Scholastic: “When students have access to books they enjoy reading, they read.”

We know for sure that if we simply say a shorter phrase — “When students have access to books” — they do NOT read. Plenty of failed interventions here. James Kim writes:

As part of the National Reading Panel’s (NRP) report, Teaching Children to Read (2000), a committee of reading researchers reviewed 14 studies that focused on the effects of a “widely recommended approach to developing fluent readers encouraging children to read a lot” (p. 3-21). In these studies, students usually chose their own books, read silently on their own, and received little or no feedback on the selection of books or the reading activity from teachers, parents, or peers. The NRP (2000) found little evidence that giving children more books and encouraging them to read more improved reading achievement.

When you attach the phrase “that they enjoy reading,” well, then things become close to tautological.

It’s like the way pre-K is now argued in the USA. “Children who have access to high quality pre-K do well.” Yep. But most pre-K is not high quality. So most pre-K programs do not seem to help.

I went to the underlying paper from Scholastic’s brief, the 2012 “Is the Library Important?” paper.

It has been firmly established that more access to books results in more reading and that more reading leads to better literacy development (Krashen, 2004).

Hmm. That “firmly established thing” seems to cut against the NRP finding. Maybe I’m missing something.

I read up a bit on Krashen. Learned he is against teaching vocabulary, putting him at odds with a bunch of other scholars. His argument is instead about pleasure reading.

(My personal “gut” leans in this direction too — not pleasure reading in lieu of vocab, but large amounts of it. Though my gut has never been subject to an RCT).

In describing Krashen:

Free voluntary reading (FVR) is the reading of any book (newspaper, magazine or comic) that students have chosen for themselves and is not subject to follow-up work such as comprehension questions or a summary. Krashen (2003) makes the claim that Free voluntary reading ‘may be the most powerful educational tool in language education’. It serves to increase literacy and to develop vocabulary.

Extensive voluntary reading provides non-native students with large doses of comprehensible input with a low affective filter, and thus is a major factor in their general language acquisition.

Krashen’s research has led many schools to implement in-class reading programmes such as SSR (Sustained Silent Reading). Investigations conducted by the US National Reading Panel (2000) did not find clear evidence that these programmes made students better readers or encouraged them to read more. Some educators (see Klump, 2007) believe that SSR is not the most productive use of instructional time.

Krashen’s response is that the NRP’s research was flawed and that SSR does indeed result in better readers and more reading.

Krashen’s response seems quite possible to me. For example, my own experience has been the literature on tutoring is quite mixed. But at MATCH we’ve been able to generate gigantic gains now measured by 2 economists, Harvard’s Roland Fryer (Houston) and UChi’s Jens Ludwig (Chicago). Just because something was implemented badly by the traditional schools doesn’t mean it can’t work.

3. Here’s a 2008 effort that was studied as an RCT: Training parents to help their children read.

What do you think happened?

Positive result, but small.

For children’s word reading outcome, the values for the effect size and the regression coefficient were relatively small.

4. Here’s a month-long in 2013 intervention, also as an RCT, by some JPAL-affiliated scholars:

We show that a short-term (31 day) reading program, designed to provide age-appropriate reading material, to train teachers in their use, and to support teachers’ initial efforts for about a month improves students’ reading skills by 0.13 standard deviations. The effect is still present three months after the program but diminishes to 0.06 standard deviations, probably due to a reduced emphasis on reading after the program. We find that the program also encourages students to read more on their own at home.

Interesting. They were able to find an effect in a month. That might be helpful for us. One of my boss’s questions is: how quickly could we find an effect? I had been saying “two years.”

Hmm. Geordie, we should probably dig in here, to understand what happened.

The authors write, to summarize the state of research as of 2013, that:

We know resources can affect improvements when paired with a larger array of inputs (Glewwe and Kremer, 2006). We do not know which inputs are necessary. For reading in particular, studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of large comprehensive changes. Banerjee et al. (2007), which studies an Indian remedial education program, is a good example. The intervention causes students’ reading skills to improve, but because the intervention changes the educational environment along multiple dimensions—additional teachers, new pedagogical methods, new curriculum, changes to organization of the classroom, and additional resources—we cannot identify which components cause the improvements.

5. Finally, hat tip to Matt Levey, the following is not an RCT. It’s from a website called Test Your Vocabulary.

They write:

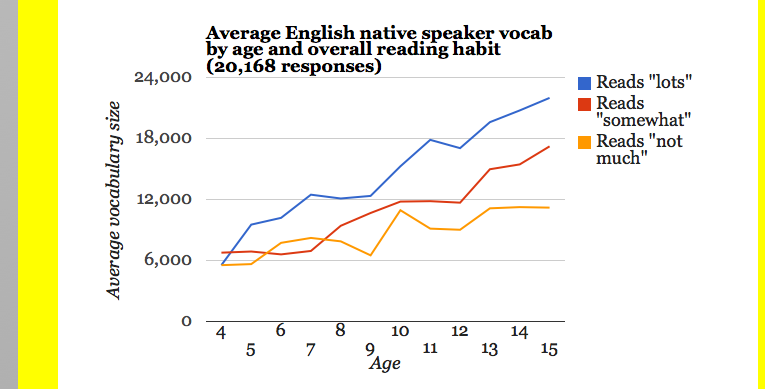

The data is still pretty noisy because of fairly low participation levels (between the ages of 4 and 8, there are still only between 140 and 260 responses per age, while by age 12, there are already more than 1,500).

However, the overall picture is still pretty clear: at around age 4, when children are only first starting to read (at best), average vocabulary levels are roughly equivalent in relation to reading habits (as one would expect) — at around 6,000 words. Then, it’s between the crucial ages of 4–15 where reading makes all the difference in the rate at which children increase their vocabulary. We can calculate the differences, although these should be taken as “ballpark approximations” at most, given the noisiness of the data:

Reading habits Vocabulary growth per day, ages 4–15

Reads “lots” +4.1 words/day

Reads “somewhat” +2.6 words/day

Reads “not much” +1.4 words/dayThis is a fascinating finding, as it tells us that vocabulary growth is drastically affected by the amount children read. By age 15, this has resulted in a difference of 5,000–6,000 words between each level, and children who read “lots” have almost double the vocabulary of children who read “not much”. Obviously, this will affect school performance, SAT scores, and so on — and it’s a difference accumulated throughout all of childhood.

(However, keep in mind that these learning “rates” are based only on averages across all our survey respondents — they are not representative of the population as a whole. Also, the rates are “average” only — we also don’t have enough data to separate them out into percentiles yet. 4-year olds who start out with larger vocabularies of 7,000 words, or smaller vocabularies of only 3,500 words, could likely show different growth rates, and other factors besides reading habits surely affect vocabulary growth as well.)

Now this stuff is entirely self-selected — people who choose to visit a website. Still, the relationship is striking.

This is more what I believe in my gut. The act of reading systematically leads to vocabulary increase in a way that accrues steadily over time.

6. A Harvard scholar named James Kim argues against the Krashen point of view.

He argues:

To close the literacy gap in the elementary and middle grades, schools should consider using systematic vocabulary instruction throughout the school day and during expanded learning time. (Contra Krashen above).

What’s that?

To implement systematic vocabulary instruction, educators need to accomplish three goals: sustain a school-wide vocabulary program, assess student knowledge, and help teachers target the right words during instruction.

And here’s his paper arguing that to fight “summer reading loss,” an intervention he designed might work, which mails books home to kids (among other things). That approach is currently in a large-scale RCT funded by IES.

*

We’ve got a lot of thinking to do here.

Michael, with all due respect, you’ve left out the most important things: that some books are better than others and that those better books (because of text complexity and content) provide the tools for the domain mastery (including the rich vocabulary that goes with it) that is the key to future success (and, more than likely, success on standardized tests). The failure to measure content quality (and consistency) is one reason you don’t get any studies showing that reading any ol’ thing helps.

Peter, I got the CK thing, fear not. Ask Robert Pondiscio.

Count on to pay far more for weekends, peak summer season travel season and far more private accommodations.